Using Comprehensible English – for Secondary School (Online Regional Training)

- Date

- TBC

- Price

- £45

- Type

- Online course, Regional training

- Location

- Online

Explore our seven calls to action for the new Government to integrate children who use EAL.

Comprehensible English is classroom language that creates access to all aspects of the curriculum for learners using English as an Additional Language (EAL). When teachers use comprehensible English to give instructions, present content, set tasks, and deliver feedback, they create the conditions for learning English and learning through English.

Comprehensible English doesn’t mean oversimplifying: learners need exposure to all levels of vocabulary and to the language structures that are particular to the subjects they are studying if they are to access the curriculum successfully. But, to make sure that English is comprehensible, teachers need to be conscious of how they speak, and of the language choices they make, so that learners at all levels of English proficiency can make sense of what they need to do and know.

1. Clear and explicit instructions:

Pauline Gibbons (2002) reminds us that one of the tasks that learners using EAL struggle with the most is following and remembering a list of instructions. To make instructions more comprehensible, teachers can do the following:

2. Contextualised and scaffolded academic vocabulary:

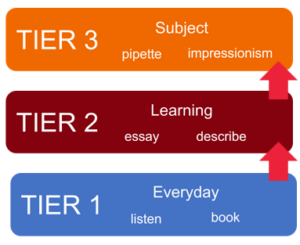

Research conducted by Beck and colleagues (2013) categorised classroom language into three tiers. Tier one vocabulary are words that appear frequently in everyday use, for example "listen", "sit", "book". Tier two vocabulary are words that are used generally for learning, for example, "essay", "describe" or "dictate". Tier three words are those that are specific to a subject, for example, "impressionism" in art or "pipette" in science. As Robert Sharples (2021) explains, some words appear in more than one tier and need to be taught explicitly.

Research conducted by Beck and colleagues (2013) categorised classroom language into three tiers. Tier one vocabulary are words that appear frequently in everyday use, for example "listen", "sit", "book". Tier two vocabulary are words that are used generally for learning, for example, "essay", "describe" or "dictate". Tier three words are those that are specific to a subject, for example, "impressionism" in art or "pipette" in science. As Robert Sharples (2021) explains, some words appear in more than one tier and need to be taught explicitly.

Older learners, who are in the earlier bands, will have significant gaps in tiers 1 and 2, and these will need to be explicitly taught.

To support vocabulary development, teachers can do the following:

When introducing new terms, say them slowly and with emphasis, and sound out each syllable clearly, for example: suff-ra-gette.

In addition to using the strategies provided above, there are features of classroom language that can affect how comprehensible classroom English is.

Top tip: Repetition of instructions or content can reinforce language and give learners multiple opportunities and time to absorb what it is they must do or know. For example, repeat a set of instructions by saying them first, then asking children to repeat them back to you, as you write them on the board.

After several decades of research into how learners acquire a new language, Lightbown and Spada (2006) concluded that “[L]anguage which is modified to suit the capability of the learner is a crucial element in the language acquisition process.” They showed that when adults modify and control the language they use, as families and teachers do with young children, for example, they create greater opportunities for learners using EAL to understand and participate actively in their learning.

Learners using EAL have a double challenge: they need to learn English and learn through English. Using comprehensible English in the classroom provides these learners with much-needed support and multiple opportunities to hear and read new vocabulary and new language structures in context. As Gibbons (2002) has shown, scaffolding learning using strategies such as contextualising and modelling new vocabulary, speaking slowly and clearly, and supporting talk with visuals and gestures, can be effective in creating access to the world of learning in English.

Learners who use EAL are a heterogeneous group. Multiple factors, including the previous education they may have had, and the stage that they entered schooling in the UK will impact on the linguistic challenges they face and on the amount and type of support they will need to access English. When teachers are aware of the language choices they make and use multiple strategies in order to make classroom English comprehensible, they can provide that “crucial element” that Lightbown and Spada identified to successfully break down barriers to learning.

Beck, I., McKeown, M.G. and Kucan, L. (2013) Bringing Words to Life (Second edition). New York: Guilford Press.

Gibbons, P. (2002). Scaffolding Language, Scaffolding Learning. Teaching Second Language Learners in the Mainstream Classroom. Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Heinemann.

Lightbown, P. M. & Spada, N. (2006). How Languages are Learned. (Third edition). Oxford. Oxford University Press.

Sharples, R. (2021). Teaching EAL. Evidence-based Strategies for the Classroom and School.