Teaching EAL Learners in English Literacy, English and English Literature

Multilingual children who are learning English as an Additional Language (EAL) bring valuable knowledge to the learning of their new language. They have already acquired knowledge of the sounds, vocabulary, and grammar of their home language(s) and learnt how to use them in different contexts, with different audiences and for different purposes. If they have learnt to read and write in their language, they will have phonetic and syntactic knowledge, know the letters/characters of their alphabet/writing system and how they combine to make words, and may have acquired complex school literacy practices in reading and writing. Children using EAL can transfer this language knowledge, along with their semantic knowledge (knowledge of the world), to the learning of English.

But learning English and studying English literature will present challenges. For learners using EAL to transfer their existing knowledge about language to learning subject English successfully, they need to learn the vocabulary and registers of multiple contexts, and to access meaning in English storybooks and literary texts, that reflect worlds that may be far removed from their own. In addition, where multilingual learners are new to the English education system, they may need support adjusting to subject demands to express their own ideas and opinions, and personal responses to texts, if their previous learning has been marked by a more teacher-centred pedagogy.

Language support that is targeted to the unique needs of each individual learner is therefore essential.

What are the challenges for EAL learners in English and English literature lessons?

When we consider the challenges that learners using EAL face, it is helpful to consider challenges at three levels: word, sentence, and text. This can help teachers to plan targeted language support.

Word level

- New vocabulary: learners will encounter a large amount of spoken and written text in English and English literature, across a wide range of genres, from fairy tales and stories to poetry, plays, and non-fiction. They will need multiple strategies to work out the meaning of new words.

- Subject-specific vocabulary: learners will need to understand the words of literature study, such as character, assonance and hyperbole, and the words of subject English such as suffix, homonym, debate, and syllable.

- General academic vocabulary: learners will need to understand the meaning of words such as summarise, analyse, and justify; terms they may know from other subjects, but for which they will need the precise requirements for subject English and literature study.

- Vocabulary from a range of varieties, including standard English, slang, and colloquial language: learners will need to work out the meaning of common English expressions, such as “pop on your coat”, which may be confusing. English storybooks and literary texts may contain words and phrases, for example in dialogue, from English dialects, or may contain archaic language, all of which will pose challenges for learners who are acquiring English.

Sentence level

- Sentence types: learners will encounter multiple sentence types, of varying complexity, that perform a range of functions in texts. Sentence types range from simple to complex-compound sentences and include exclamations, rhetorical sentences, and imperatives, among other types.

- Description and idiom: stories and novels may contain descriptive sentences, with multiple adjectives, for example, and English literature is laden with figurative and idiomatic language that adds ambiguity and may be confusing, even for learners who are fluent in English.

- Experimental forms: poetry in all its forms presents challenges to learners developing language knowledge in English, especially where writers use unconventional and experimental sentence forms.

Text level

In subject English, learners will encounter a wide range of text types, with varying structure, register, syntax, and other discourse features. Reading storybooks and literary texts, they will be required to make inferences as they read. They will need to penetrate the world building (Nancarrow, 2017) that writers create as they describe settings, atmosphere, and contexts in stories. Reading these texts requires using language and cultural knowledge that multilingual learners may not have.

Learners will also have to learn a range of cohesive devices, as they are used in different genres, such as “Once upon a time…” in fairytales, and more complex devices in literature and poetry such as ellipsis and substitution.

How can teachers support EAL learners to meet the demands of English and English literature?

Teachers can help EAL learners in English and English literature lessons by using these strategies:

1. Draw on each learner’s existing language knowledge and skills.

Some teachers are wary of creating opportunities for learners to use the whole range of languages they know in English lessons, as they may feel it causes confusion or interference. However, our knowledge of the way that bilingualism works, where effective bilinguals move between the languages they know as they negotiate and make meaning in a new language (cf. Garcia, 2013), shows us that drawing on what you know, in the languages you know, creates a foundation for learning a new language (Hillcrest, 2021).

Here are some strategies that teachers can encourage and plan for:

Translanguaging

Children and young people move between languages as they negotiate meaning in their new language. Teachers can create opportunities for their multilingual learners to, for example:

- Tell stories using all the languages they know.

- Work in a group that shares the same language to discuss a topic using their preferred language, as they make sense of English.

- Annotate a text using both their preferred language and English.

- Plan writing and prepare drafts, using the languages they know.

For further ideas, see Translanguaging.

Using bilingual dictionaries

Where learners have good reading ability in their home language, or in another language they have learnt, bilingual dictionaries provide excellent support for building vocabulary in English (see Bilingual dictionaries). Keep bilingual dictionaries in your classroom and encourage learners to access dictionaries on their mobile devices. For learners who have limited literacy in their home language, visual dictionaries can be useful.

Encourage learners to create their own bilingual dictionaries, with translations of key words they encounter in their reading or need to use in speaking and writing.

Because many English words have multiple meanings, and can be used in different ways, in addition to consulting a dictionary, multilingual learners will need to learn strategies for building word knowledge, including by using contextual clues.

An additional resource is Immersive Reader in Office 365. It can be used to create visuals for the text, translate text, and read the translated text aloud for multilingual learners who are not literate in their home language.

Comparing and building metalanguage awareness

Comparing word meanings between languages, considering grammar rules and patterns, and contrasting the formats and structure of text types will all help multilingual learners develop metalanguage awareness, which will strengthen their understanding of how English works. Where learners can use translation software, and find the meaning of words and phrases, they can make comparisons with the way English works. Where possible, create opportunities for learners to work with others who share the same language background, to promote learning through discussion and sharing of knowledge.

2. Prepare activities ahead of reading.

Whether your learners are reading storybooks in Key Stage 1, or a Shakespeare play in Key Stage 4, there will undoubtedly be language that draws on cultural knowledge that is new to them. For example, the opening chapter of The Railway Children refers to pantomimes and a doll’s house, and a central theme of The Woman in Black refers to a haunting. Teachers need to identify the vocabulary and storylines that learners using EAL will have difficulty understanding, and design pre-reading activities to explain those references, for example:

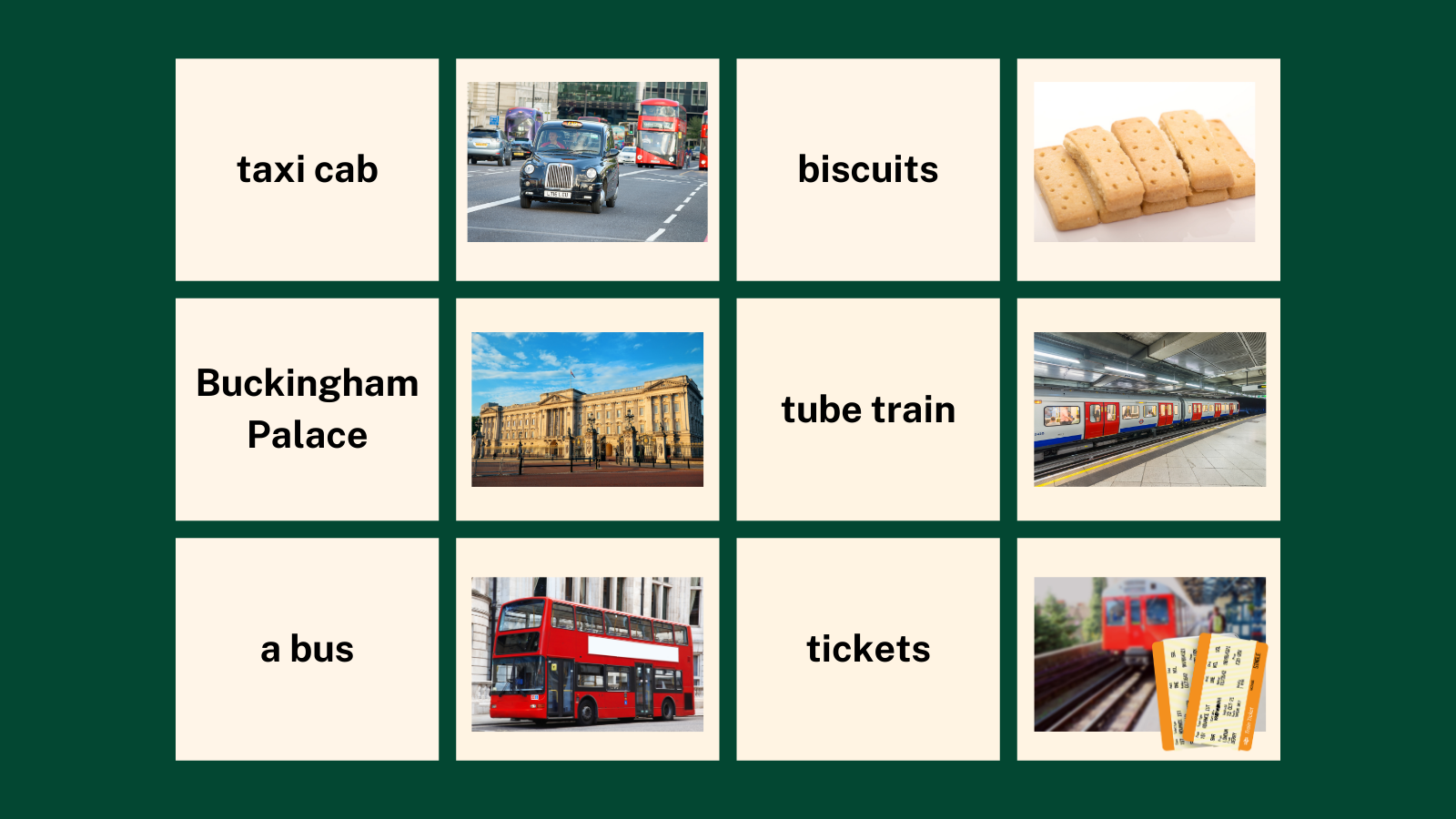

- Make words mats with key words and pictures, for example like this one for The Boy at the Back of the Class

- Create opportunities for learners to share information about related cultural references they are familiar with, like describing a supernatural being from their culture, in preparation for the supernatural theme in The Woman in Black.

- Use the text title or first sentence to predict what the text is about, as a way of building a context for the unfamiliar references. For example, for the poem, Poppies, use visuals and explain the historical significance of poppies in British society, to support a prediction activity.

- Arrange a reading of the text in the preferred language, before reading it in English.

- Summarise the text that is to be studied, and provide a translation of the summary.

3. Provide scaffolding.

Identify common errors that your learners make, for example with subject verb agreement, or a difficult tense, like the past perfect, and design comprehension and composing activities with scaffolding, like sentence frames.

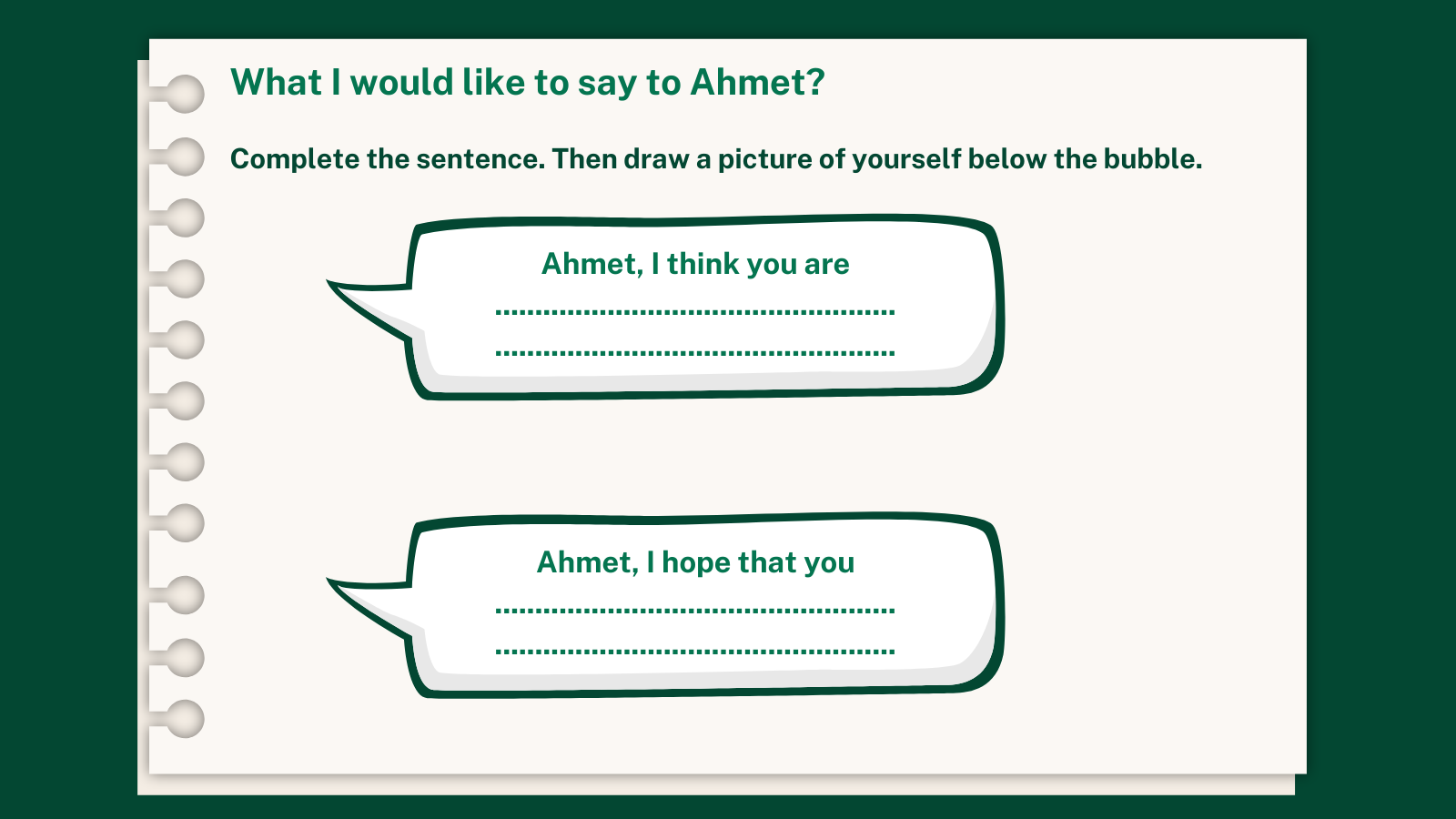

You can use sentence frames to help learners structure their responses to the texts they study. Here is an example of sentence frames for expressing responses about the titular character in The Boy at the Back of the Class.

For further ideas, see: Speaking and Writing Frames.

4. Use multimedia.

Make use of recordings, for example audiobooks of favourite stories, or set texts, where learners can listen to dramatised versions, more than once if they need to. Listening to reading aloud will help to consolidate understanding, plus help with pronunciation. Watching film versions of literary texts will help build contextual knowledge of the text and bring characters to life. An added bonus is subtitles in a language the learner knows and can read. Listening to songs in early years and Key Stage 1 will add enjoyment, while children build vocabulary knowledge.

Where learners can access a translation or film version of a set text before the class studies the text, (or read a simplified version), they will know the gist of the story, which will help them to participate in discussions and investigations of the literary aspects, including explorations of the characters’ motivations and key themes. This preparation is particularly useful for longer texts.

5. Draw on your existing practice.

As English teachers, you will already have an arsenal of useful strategies to guide your learners to work out the meaning of new words, use inference as they read storybooks and literary texts, understand text structure, and remember plot lines. Many of the ideas in the Faster Read model of reading (Sutherland et.al., 2024), including reading aloud, modelling text engagement strategies and using graphic organisers to illustrate text structure, can be usefully employed to support multilingual learners who use EAL.

6. Promote reading for pleasure.

Encouraging children to read widely and beyond the official curriculum can support learning in English. Reading more widely can build vocabulary knowledge and serve to boost a child’s identity as a reader. Make sure you get to know what your multilingual learners’ interests and talents are, so that you can recommend fiction and non-fiction they may enjoy. In early years and primary, add dual language storybooks to your classroom library, so that children can enjoy reading in the languages they know and start to familiarise themselves with the accompanying text in English.

How can teachers make a fair assessment of EAL learners’ progress and attainment in English and English literature?

When a multilingual learner is new to your school, it is good practice, after they have had two or three weeks to settle in, to conduct an assessment of their knowledge and skills in English. Using The Bell Foundation Assessment Framework will help you to identify key language knowledge and skills each learner has or needs to acquire and will help you to identify the precise language support they need to access the language in the texts you are teaching.

In addition, try to find out from the learner and, where possible, their family what, if any, learning of English the new learner has undertaken before coming to your school. Additionally, older learners may have learnt about literary techniques and literary analysis in their home language and be in a good position to transfer that knowledge to English.

As learners set out to learn English, plan opportunities for them to use visual approaches, including drawing and collage-making, to show their knowledge, for example of plot outlines in stories, or contrasts between characters.

As literacy and language teachers you are well-placed, with the knowledge and awareness you bring of how English works, to anticipate and prepare for the challenges that learners using EAL face. By setting high expectations, you will support them to overcome those challenges and succeed.

Useful links

Building Vocabulary - The Bell Foundation (bell-foundation.org.uk)

DARTs - The Bell Foundation (bell-foundation.org.uk)

EAL Assessment Framework - The Bell Foundation (bell-foundation.org.uk)

Focusing on grammar patterns - The Bell Foundation (bell-foundation.org.uk)

How to Provide Multilingual Support in the Classroom - The Bell Foundation (bell-foundation.org.uk)

Is it English as an Additional Language, a language disorder, or both? (Webinar) (youtube.com)

National Literacy Trust | UK Literacy Charity

Scaffolding - The Bell Foundation (bell-foundation.org.uk)

Speaking and Writing Frames - The Bell Foundation (bell-foundation.org.uk)

Substitution Tables - The Bell Foundation (bell-foundation.org.uk)

Translanguaging - The Bell Foundation (bell-foundation.org.uk)

References

Garcia, O. (2013). Theorizing Translanguaging for Educators. In C. Celic, K. Seltzer, & L. Ascenzi-Moreno (Eds.), Translanguaging: A CUNY-NYSIEB guide for educators (2nd. Ed.): 1-6. The Graduate Centre at The City University of New York.

Gibbons, P. (2002). Scaffolding Language Scaffolding Learning. Teaching Second Language learners in the Mainstream Classroom. Portsmouth. Heinemann.

Hillcrest, D. (2021). Academic benefits of translanguaging. MinneTESOLJournal, 37(2).

Nancarrow, P. (2017) The Language of Literature. EAL Journal. Summer 2017: 41-43.

Pim, C. (2012). 100 Ideas for Supporting Learners with EAL. London. Continuum Books. o

Sutherland, J., Westbrook, J. & Oakhill, J. (2024) A Faster Read Model of Reading. Sussex University. CPD for Teachers on the Faster Read : Faster Read Project : ... : Centre for International Education (sussex.ac.uk)