Blog: How to support trainee teachers to teach EAL pupils

As multilingualism and English as an Additional Language become an integral feature of school life, how can initial teacher training (ITT) programmes prepare student teachers to work within linguistically and culturally diverse settings? Sheila Hopkins advises.

Key sections in this article:

- How many pupils use English as an Additional Language in the UK?

- A lack of confidence and experience in EAL teaching

- What this means for ITT programmes

- Support for EAL content in teacher education

- Incorporating EAL into ITT programming

- Conclusion

- Further information & resources

Britain has always been multicultural and multilingual; greatly benefitting from diversity over the centuries. Today is no exception. In fact, many British cities are what we now call superdiverse communities where people with vastly different languages, cultures and backgrounds live side by side enhancing our schools and neighbourhoods.

How many pupils use English as an Additional Language in the UK?

The Department for Education’s (DfE) January 2022 School Census provides us with the current EAL landscape in the UK. Almost 1 in 5 pupils (19.5%) in the UK school system, nursery through secondary, are learners who use English as an Additional Language (EAL).

This number rises to nearly one third of pupils in nurseries (29.1%), most of whom were born in the UK. These numbers reflect the multilinguistic landscape which our current student teachers will enter.

In an effort to determine the extent to which EAL is taught in Initial Teacher Training (ITT) programmes, and how well student teachers are prepared to work within multilinguistic settings, The Bell Foundation commissioned a study on EAL in ITE with the University of Edinburgh (Foley et al, 2018).

A lack of confidence and experience in EAL teaching

Key findings show that while prevailing policy (National Curriculum, 2013) has prioritised integration and inclusion, little attention has been given to expanding the knowledge-base of trainee teachers to enable them to address the English language and literacy needs within linguistically and culturally diverse classrooms.

The report provides evidence showing many trainee teachers and teacher educators feel that they lack confidence and experience as they work to address the learning needs of pupils using EAL.

Significantly, one-third of trainee teachers felt they had “little” or “little to no” understanding of the English language and literacy needs of multilingual learners.

This scenario is particularly concerning as Standard 5 in the DfE’s 2011 Teachers’ Standards specifies that teachers must “have a clear understanding of the needs of all pupils, including … those with English as an additional language”, and that they must “be able to use and evaluate teaching approaches to engage and support them”. In this regard, methodologies that are based solely on monolingual English speakers are no longer fit-for-purpose (Leung, 2014).

What this means for ITT programmes

For school-based ITT programmes, this means that teachers with key mentoring and training responsibilities will need to have or develop the necessary expertise for guiding and supporting trainee teachers in working with multilingual learners.

In identifying further learning opportunities, such teachers should be mindful of discourse and practices that perpetuate an orientation of seeing bilingualism as an obstacle or problem (and English as a solution) rather than multilingualism as a valuable resource and key marker of a learner’s identity – making the use of all pupils’ languages something to promote in schools.

The Bell Foundation has developed free training modules specifically for ITT providers. This article describes the modules’ connection to the ITT Core Content Framework (DfE, 2019), their content and design features and provides recommendations for their infusion into existing ITT programming.

Support for EAL content in teacher education

Although the ITT Core Content Framework (CCF) defines the minimum entitlement of training for all trainee teachers, it is highly and deliberately general in its approach. This means that responsibility for adequate and appropriate curricula development lies with individual ITT providers.

The Bell Foundation has a guidance document in line with the CCF which offers evidence-informed EAL content recommendations for inclusion in ITT curricula as well as a series of three, free-to-access, EAL modules and materials for teacher educators to use within ITT programming.

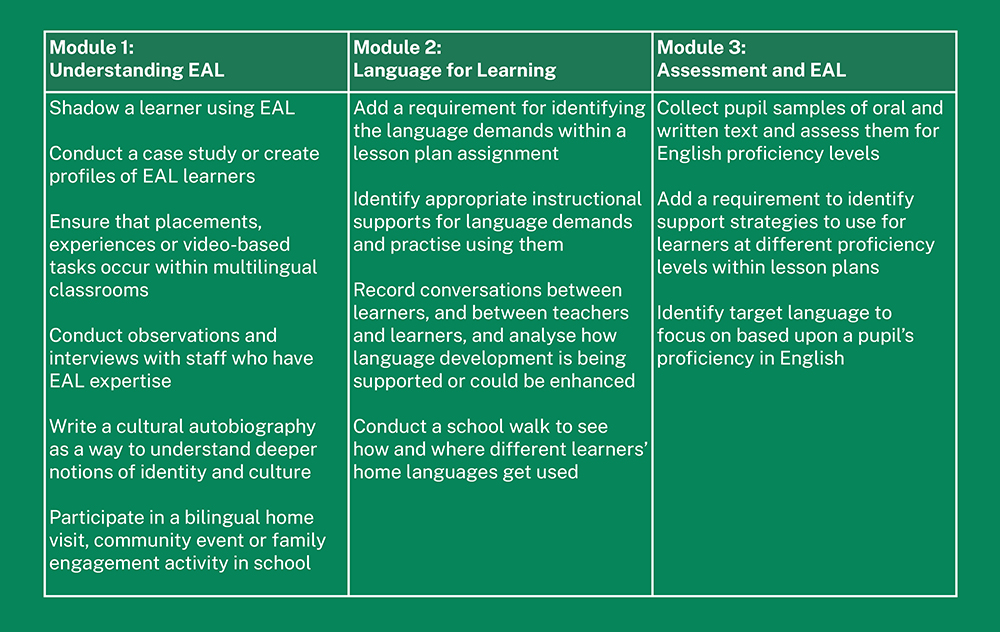

- Module one: Understanding EAL; contexts, policies and pedagogy.

- Module two: Language for learning.

- Module three: Assessment and EAL.

Module three has recently been launched and a webinar recording is available for ITT providers to explore how it might be used.

Each module is designed to build upon trainee teachers’ personal experiences as they make links to new evidence-informed content through meaningful activities and through application to their practice.

As ITT programmes differ around the UK, the modules have design features that enable tutors to adapt materials, making them relevant to their training context and the learning needs of their student teachers.

These include duration options (60 or 180 minutes), phase-specific options, and content options (core and supplementary content).

Incorporating EAL into ITT programming

The ITT modules aim to provide trainee teachers with a grounding in EAL knowledge and strategies. However, the bulk of EAL-related pedagogical principles and practices should ideally be infused throughout an ITT programme.

In principle, such a dual approach ensures that EAL is given a central focus across all core concerns and individual subjects of a teacher education programme, rather than being treated as a “bolt-on” addition to existing programmes (Foley, 2018).

In this way, language development is incorporated into the teaching of all subjects and into areas such as scaffolding, feedback, assessment and group work.

To achieve this, ITT programmes may need to consider matters that involve curriculum mapping, Continuing Professional Development (CPD) for key mentoring and training staff, and/or partnership building with EAL experts in their schools or from other schools and local authorities.

Finally, the chart below provides further suggestions for how learning from the aforementioned ITT modules can be built upon and infused throughout an ITT programme.

Conclusion

As there are over 1.6 million learners recorded as using ‘EAL’ in England it is likely that many newly qualified teachers will be working in multilingual classes, and therefore it is vital that EAL teaching is incorporated into ITT training in order to equip new teachers with the necessary skills needed to meet every student’s needs.

- This article first appeared in Headteacher Update and SedEd on 25 April 2022.

Further information & resources

- DfE: Initial teacher training (ITT): core content framework, November 2019

- Foley et al: English as an additional language and initial teacher education, University of Edinburgh, October 2018

- Leung: Researching language and communication in schooling, Research Portal, King’s College London, 2014.